A realistic plan to phase out RVs as shelter in Berkeley: Op-ed

Capping the number of large vehicles being used as shelter in Berkeley will stop the growth and lead to longterm solutions, Amber Whitson argues.

Editor's Note: TBS periodically publishes guest essays from community members on issues of concern. Today's piece was written by Amber Whitson, an activist, advocate, dog mom and survivor who has lived in Berkeley and Albany for the past 29 years.

The city of Berkeley has made it quite clear that there is no money in the budget and no space within city limits for a safe RV parking lot.

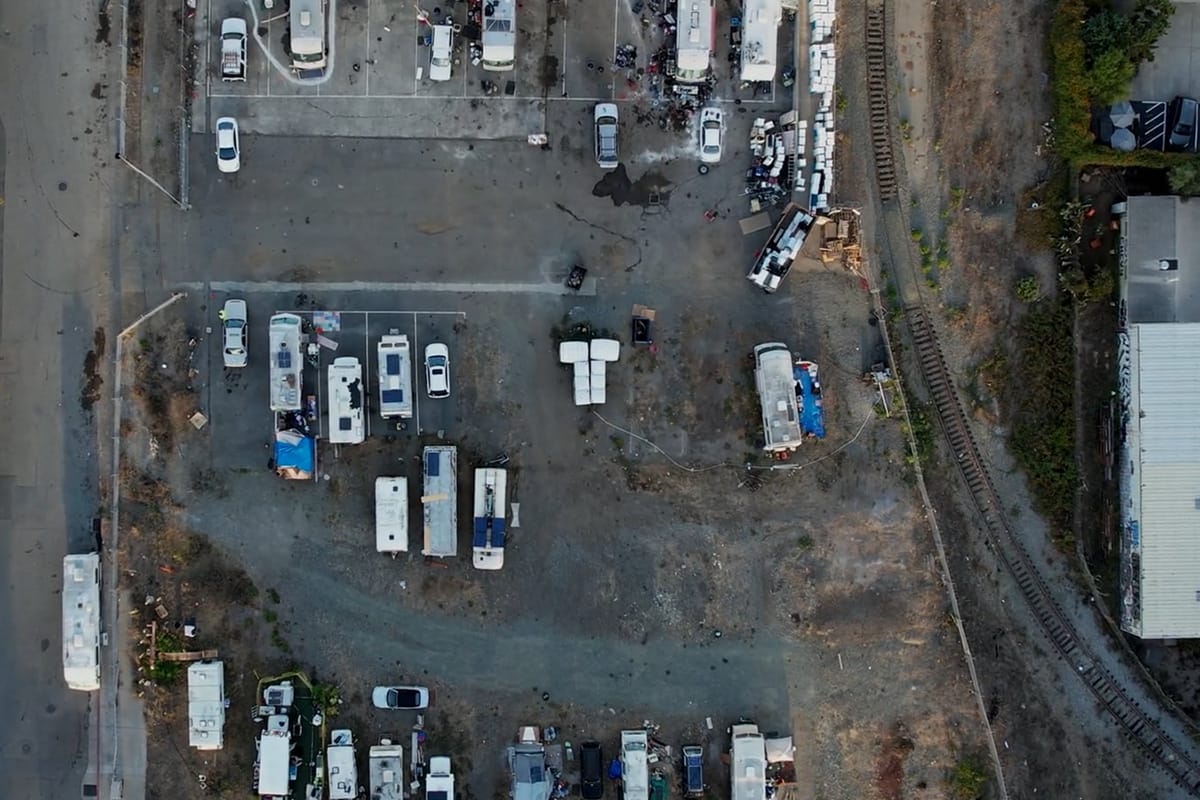

At the same time, Berkeley has an unknown (and occasionally growing) number of RVs and trailers being used as shelter throughout multiple neighborhoods (primarily in West Berkeley).

There is no cap on the number of these vehicles that are allowed to park in Berkeley. There is no defined framework for how to reduce (or at least limit) that number. Meanwhile the city is currently involved in multiple lawsuits related to how it treats unhoused residents, including vehicle-dwellers.

(Full disclosure: I am a plaintiff in one of those lawsuits.)

Both housed and unhoused residents are demanding action.

The response to the outcries of housed people has been dog-and-pony shows, like the "list of potential locations" that might host sanctioned encampments (a vast majority of which are currently in use or topographically infeasible), in order to demonstrate just how hard the city is working to respond to their needs.

The city has been responding to unhoused people with expensive abatement actions (aka sweeps) which are labor-intensive, and legally risky.

Sweeps displace people to other parts of the city, sometimes relegating them to tents and sidewalks when their vehicles are impounded. These sweeps expose the city to the risk of costly litigation. They do not reduce the underlying number of homeless people in Berkeley.

Right now, Berkeley is trying to reduce a population that has no defined ceiling.

Over the past seven or eight years, I have suggested a different approach on numerous occasions: create a permit program for the large vehicles currently being used as shelter and cap the number of those vehicles parked on Berkeley streets.

The idea is simple.

Conduct a defined census. Issue permits only to those vehicles verified during that census. Cap the number of overnight large vehicle permits at that number.

No waitlist. No expansion.

From that point forward, the population of large vehicle dwellers becomes finite.

Stabilize first. Reduce second. Sunset to zero.

Right now, Berkeley is trying to reduce a population that has no defined ceiling. That makes enforcement chaotic and politically volatile. It's a game of Whack-a-Mole where the stakes are high and the goalpost is forever moving.

A large vehicle shelter permit (LVSP) program would immediately:

- Freeze growth at the census number

- Establish basic, enforceable standards

- Provide predictability for housed residents and vehicle-dwellers alike

- Reduce legal exposure by creating consistent, documented procedures and accountability

- Allow the Homeless Response Team to focus on housing exits rather than perpetual displacement

Under this model, the number of large vehicles would never increase beyond the original census count and would decrease as people move into housing.

The end goal is not permanent street habitation. The end goal is zero overnight parking of ALL large vehicles once everyone currently sheltering in them is housed.

This proposal does not create a new right to park. It creates temporary, regulated permission tied directly to housing transition.

How large vehicle shelter permits would work

Step 1: Establish the ordinance

The Berkeley City Council would adopt an ordinance creating the large vehicle shelter permit program that:

- Defines "large vehicle" (RVs, trailers, etc.) as those above a set size threshold, number of axles, etc.

- Applies only to city streets and the public right-of-way

- Sets objective, behavior-based compliance standards

- Establishes the permit cap equal to the verified census count

- Creates a clear enforcement ladder and appeals process

This regulates conduct and public-space impact — not homelessness as a status.

Step 2: Conduct a time-limited census

The city would announce a 10- to 14-day census window with advance notice.

During that period:

- Field teams will document every large vehicle being used as shelter

- Record plate/VIN if visible, vehicle type, distinguishing characteristics and block location

- Photograph for verification

- Leave a census notice explaining next steps

To prevent inflow gaming, eligibility of any vehicles not documented during the census would require verified presence during the census window or a documented recent presence in Berkeley (with "recent" being defined as within a specific number of months).

The final verified total becomes the cap.

Growth stops there.

Step 3: Registration and permit issuance

Vehicles verified during the census would have a defined registration window.

Registration for the permit would require:

- Basic vehicle identification

- Proof of control over the vehicle (with a conditional pathway for documentation issues)

- Agreement to minimal compliance standards

A brief curbside inspection would confirm:

- No sewage or graywater discharge

- No excessive property footprint

- Sidewalk clearance maintained

- No obstruction of hydrants or traffic lanes

- No hazardous mechanical conditions

Permits would be time-limited and renewable only while compliant.

Step 4: Predictable enforcement

The enforcement ladder would be clear and transparent:

- Written warning with fix-it period

- Citation if not cured

- Permit suspension after hearing opportunity

- Tow only for immediate hazards or repeated noncompliance

No surprise sweeps. No mass displacement. No confiscation without notice.

For housed residents, this means visible compliance checks and enforceable standards. For vehicle-dwellers, it means rules that are consistent rather than arbitrary.

The city could publish quarterly metrics: number of permitted vehicles, warnings issued, cures completed, suspensions and successful exits to housing. That level of transparency would replace speculation with data.

Why this is more feasible than the status quo

Berkeley previously spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on a time-limited safe parking program that served a limited number of large vehicles. The city’s broader homelessness-related expenditures run into the tens of millions annually.

By contrast, a capped permit program would likely cost in the range of:

- $250,000-$700,000 in one-time startup costs (IT, census staffing, ordinance drafting)

- Approximately $1 million to $2 million annually in staffing and administration

That is not trivial.

But it is materially less than repeated enforcement operations, overtime pay for Public Works, property storage processing and ongoing legal exposure.

More importantly, it creates a defined and shrinking population rather than an open-ended crisis.

The legal and political reality

Courts are increasingly scrutinizing how cities handle encampments and vehicle dwellers, particularly around notice, property handling, disability accommodation and due process.

A permit system built on objective standards, documented cure periods, and transparent appeals is far more defensible than reactive displacement.

Politically, it also provides something the current approach does not: a cap.

For housed residents frustrated by what they see as uncontrolled growth, this is the first mechanism that would immediately halt expansion. For those concerned about criminalization, it replaces unpredictable enforcement with structured regulation tied to housing outcomes.

A practical path forward

In the interest of reducing costs and preventing further criminalization, I would gladly assist in cataloguing vehicles during the census phase, and I am confident others would volunteer as well.

With the initial count completed and data turned over to the city, outreach to occupants would likely be conducted by the Homeless Response Team (or, perhaps, Options Encampment Services to address privacy concerns and coordinate services).

Berkeley cannot afford unlimited growth in street-based vehicle shelter. Right now, more than a year after the buyback program that cleared all the large vehicles from Second Street, Berkeley has relatively few people living on its streets in large vehicles.

It also cannot afford endless sweeps and lawsuits.

The city can continue paying for chaos and trying to explain its actions (and their inaction) to the courts, or it can create a controlled system that stabilizes the number of large vehicles parked on Berkeley streets and then phases it out responsibly.

A capped permit program is the most realistic way to do that.

What happens next?

At the Feb. 11 meeting of Berkeley's Health, Life Enrichment Equity & Community policy committee, committee members voted unanimously to send an item to the full City Council that — if approved — would establish regulations related to large vehicles parked on city streets.

The date for the vote has yet to be set.

As proposed, the changes would:

- expand authority to remove "abandoned" vehicles (note: the highly dubious quotation marks around the word "abandoned")

- clarify definitions (e.g. "abandoned")

- and give the city manager broader discretion over abatement timelines

The proposal also calls for:

- studying regional large-vehicle parking policies

- exploring geographically targeted restrictions in sensitive areas (like manufacturing and industrial zones, historically known for being gentle on the environment... NOT)

- considering participation in a countywide RV parking program (is there even precedent for this?)

- clarifying how encampment policy applies when no shelter is available

- and authorizing up to $250,000 in contract spending related to enforcement (because, in today's political climate: that there will always be funds for enforcement)

I showed up to the meeting and spoke my piece, along with several other Berkeley residents who would be affected by the proposal.

I warned of the very real possibility that implementing the proposed changes would not only be harmful to the unhoused residents of Berkeley, and be an added setback in their efforts to move into traditional housing, but that it would also expose the city to further legal action.

I pointed out that, if the city were to prioritize effective and proven solutions to homelessness as much as it does enforcement and legal defense, these regulations wouldn't be needed.

The proposal suggests examining the policies throughout the entire nine-county Bay Area to get suggestions for how to proceed.

What ever happened to Berkeley being the source of inspiration and innovation?

Why don't we do something that accomplishes the goals of more than one group of stakeholders and set a good example for others to follow? Why don't we lead the way by doing the right thing?

The Scanner will periodically publish guest essays from community members on issues of interest or concern. Authors who are not already TBS members will receive a complimentary membership in return. Submit your ideas to TBS.