Berkeley asks court to drop 'nonsensical' PAB lawsuit

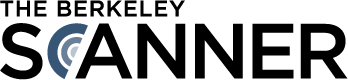

The latest city filing is the sharpest condemnation to date of Berkeley Police Accountability Board director Hansel Aguilar.

Berkeley's director of police oversight is in the crosshairs again this week in the city's latest filing about a standoff over police records.

In December, Hansel Aguilar, the city's embattled director of police accountability, sued Berkeley's police chief over records related to a police misconduct investigation.

In his filing, Aguilar argued that the city had refused to give him the documents he needed to do his job.

Since then, the Berkeley city attorney's office has pulled no punches in disputing his claims, saying Aguilar's position "reflects a troublingly poor understanding of his obligations as a public official answerable to the City Council and charged with implementing the City Charter, not to mention a decided lack of common sense."

The city has now asked a judge to force Aguilar's attorneys to explain why they shouldn't foot the bill for the case — and why Aguilar himself shouldn't be "sanctioned for filing this frivolous lawsuit."

A trial date is set for Tuesday.

On one level, the case revolves around a police misconduct investigation stemming from a homeless camp "sweep" last summer when some community members say police limited their ability to record and monitor the operation.

On another, it hinges on how police oversight works in Berkeley, including what powers the director of police oversight actually has under the city charter and whether the police chief can refuse to produce certain records.

The city's most recent legal filing says Berkeley Police Chief Jen Louis was within her rights to withhold records that did not relate to specific allegations of officer misconduct, calling Aguilar's record requests last year "overly broad."

In December, Aguilar asked the court to order the city to turn over the documents, which the city attorney's office said was "patently absurd."

The court ultimately denied his request, but set a hearing date for January so both parties could present their positions.

According to the city, Aguilar's lawsuit "should never have been filed" because Aguilar did not seek or receive permission from the Berkeley City Council to pursue it.

That created the "nonsensical" situation of the city suing itself, the city attorney's office said.

Aguilar's "assumption that he, as an appointee of the City Council, can sue the City without City Council authorization is hubristic, and wrong," the city wrote.

The city attorney's office also noted that Aguilar's misconduct investigation had ended in December, when the clock ran out on the legally imposed timeline for his probe, meaning he now has no use for additional documents.

"The Court should not order one City official to produce irrelevant records to another City official, for no purpose," the city attorney's office wrote.

The city said the police chief had, in fact, turned over all relevant records related to claims against specific officers, and that it was unaware of any misconduct findings requiring discipline that had come up as a result.

The Police Accountability Board is authorized under the charter to undertake two types of investigations: inquests on specific misconduct allegations against individual officers and more general policy reviews.

The city attorney's office argued that, under the charter, only the board — not its director — can initiate a policy review.

Aguilar's "argument that he could unilaterally initiate a review of City policies was wrong when the investigation started, and it is ludicrous now that the investigation is over," the city argued.

Aguilar, the city continued, has "been acting outside the scope of his authority since the outset of his investigation," adding that his "failure to acknowledge these clear limitations on his authority is at best grossly negligent, and at worst is a deliberate effort to distract and mislead the Court."

The latest city filing in the case is the sharpest condemnation of Aguilar to date.

But it's not the first time he's found himself on the defense since the city appointed him to the PAB director job in October 2022.

In recent months, City Council members strongly rebuked him during a public meeting over what they said was a misguided attempt to push them for action.

His own board has also taken issue with his work, at times lobbying to create its own reports due to philosophical disagreements.

In Aguilar's most recent filing, his attorneys argued that the city cannot withhold records from him unless their release is "forbidden by state or federal law" because he's legally bound by confidentiality and granted broad powers of review.

They also argued that municipal oversight boards are allowed to file lawsuits on their own "even when that action is necessary to compel officers or employees of the same City to act."

The attorneys, with Costa Mesa-based Woodruff & Smart, APC, did not respond Monday to a request for additional information.

A ruling Tuesday by the trial court could have broad ramifications if it relates to how independent Berkeley's Police Accountability Board actually is and whether the police chief has the authority to refuse its requests.

A win for Aguilar would "confer a significant benefit on the general public," his attorneys wrote, "that allegations of police misconduct be investigated by an independent body."

If the court rules against him, they wrote, Aguilar "will not be able to fulfill his duty, and the will of the voters … will be subverted."