Should Berkeley get license plate readers? Weigh in tonight.

The new automated license plate readers, which would be mounted not mobile, would be the city's first to focus on criminal investigations.

Community members in Berkeley will have a chance to give input Thursday night on a proposal to install fixed automated license plate readers around the city.

Berkeley police say the new readers will send out real-time alerts when a wanted vehicle enters the city, giving officers a better chance to head off crime in progress or even before it happens.

The city's Police Accountability Board voted in June to reject the proposal, calling for more data, better civil liberties protections, more robust policies and more clarity around costs.

The Office of the Director of Police Accountability, which staffs the Police Accountability Board, is holding a "community input session" Thursday evening on Zoom to get feedback about the proposal and provide some of the context behind it.

The Berkeley City Council is slated to consider automated license plate readers (ALPRs for short) at its July 25 meeting. But the agenda isn't final, so that date could change.

The Berkeley Police Department says a two-year trial, to include 52 ALPRs, would cost $250,000 to set up and $175,000 to run annually.

On a recent Tuesday morning, BPD shared its draft license plate reader proposal with the city's Public Safety Policy Committee, which was composed that day of council members Terry Taplin, Susan Wengraf and Rigel Robinson, who is an alternate on the panel.

The committee ultimately made a qualified recommendation in favor of the plan.

(The Berkeley Scanner reviewed a recording of the meeting after the fact to report this story.)

"No free pass" to drive around in a wanted vehicle

At the June 20 meeting, Berkeley Police Sgt. Joe Ledoux said many Bay Area cities already have license plate readers, which can have a deterrent effect and help investigators solve crimes.

ALPRs can notify police about stolen and carjacked vehicles, those wanted in connection with alerts for missing and at-risk people, and cars on local "hot lists" related to robberies, organized retail crime and shootings, Ledoux said.

Berkeley's parking enforcement officers already use mobile ALPRs to help with their jobs.

But the new automated license plate readers, which would be mounted not mobile, would be the city's first to focus on criminal investigations.

"It’s telling our officers: 'Here’s a vehicle that’s wanted. Go focus on it,'" Ledoux said. "There’s no free pass to drive around the city in a wanted vehicle that’s been associated with some sort of crime."

He said the city of Vacaville reported a 33% decrease in vehicle thefts, and a 35% increase in related arrests, in connection with its ALPR program.

According to BPD's Transparency Hub data portal, auto thefts are up in Berkeley by more than 60% this year compared to the same period last year.

And crime reports overall are up 15%.

Ledoux said ALPRs could make a dent in the auto theft numbers, scanning many more license plates than a police officer could run.

"The efficiency factor here is incredible," he said.

BPD: New ALPRs would not capture people

Last month, Berkeley officials approved new surveillance cameras at 10 intersections around the city. Police will be able to review that footage after the fact to investigate serious crimes and traffic collisions.

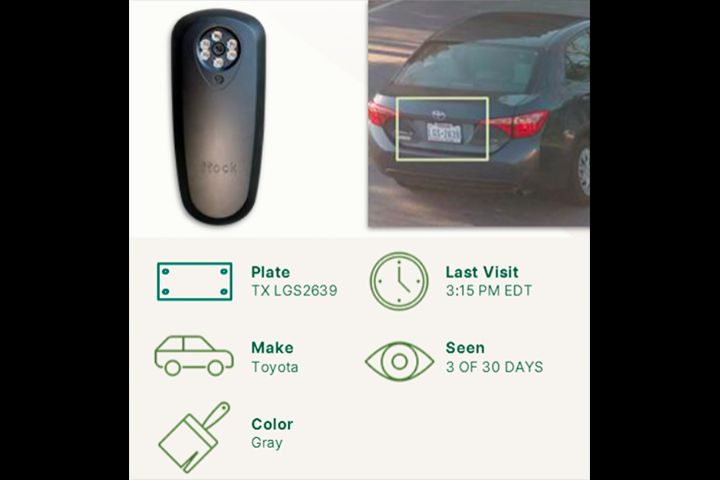

That's different from the new ALPRs, which would present still images to police along with the license plate number, vehicle make and color, the time and date of a car's most recent visit to Berkeley, and the number of times it's been in the city during the 30-day retention period.

"They do not capture people," Ledoux said. "It removes the human bias out of crime-solving by detecting objective data."

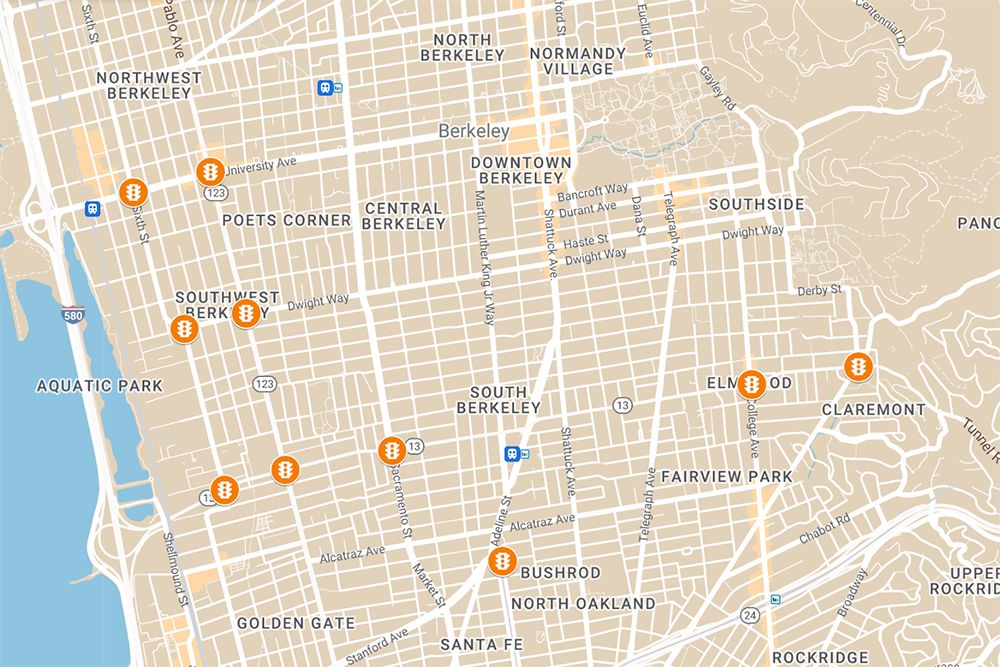

The ALPRs would be placed on thoroughfares in Berkeley rather than on residential streets.

The locations, which will be distributed around town, would be chosen with the help of the vendor if the City Council green-lights the project.

Ledoux said Berkeley initially considered more ALPR units but "scaled it way back" so the number was in line with "smaller towns" like Pinole and San Pablo.

The focus, he said, would be on "preventative and proactive" alerts about drivers coming into the city "before someone becomes a victim of robbery or has their car stolen."

Ledoux said the readers will further the city's goal of "precision-based policing": to focus enforcement activity with the help of good data.

That's particularly important, he said, given Berkeley's ongoing staffing crisis, which has led to bigger beats and fewer cops on the street this year.

"Scant data nationwide" on ALPR effectiveness

Police Accountability Board Member Kitty Calavita said the board was concerned about public safety as well as civil liberties and wanted to base city policy on reliable data.

She said the board believed BPD's ALPR proposal had not sufficiently addressed the "complexities and challenges" of those topics.

Calavita said most of the surrounding agencies have ALPRs despite there being "scant data nationwide" on their effectiveness.

"It would be good to have that evidence of effectiveness before we invest in something quite costly," she said.

Councilman Taplin, who initially brought forward the ALPR idea with colleagues in 2021, noted in his original agenda item that available research was limited: "The use of LPR technology has increased significantly in law enforcement agencies across the US in the past decade, but outcomes have been inconsistently tracked, which limits available research."

Ledoux said that's one reason Berkeley hopes to collect its own robust data through a pilot ALPR program.

BPD would publish statistics about its ALPR usage in its annual surveillance report and would also do a deeper dive after two years.

"In this trial period, the goal is to provide really rich data on the effectiveness because many people have asked, and it’s a valid question, is how effective is this technology?" Ledoux said. "It’s imperative for us to not only gather, but to do it right."

BPD says Berkeley will own its ALPR data, control sharing

Calavita said the Police Accountability Board was also concerned about whether ALPR data might be shared with states looking to investigate or prosecute women seeking abortions in California.

Ledoux said the proposal's language could be tightened to exclude sharing with agencies outside the state that seek to investigate behavior that is not a crime here.

Councilman Taplin confirmed with Ledoux that none of Berkeley's ALPR data would go into anyone else's database.

Ledoux said it would not and that, with a company like Flock Safety, Berkeley would own its own data, which would only be shared by BPD on its own terms.

That's not something every vendor offers, he said.

And while the project, if approved, will be open to all bidders, Ledoux said Flock seemed to be in high use around the Bay Area because of its strict approach to privacy, which would likely be a key selling point in Berkeley as well.

ALPR idea arose amid plans to reimagine policing

When Taplin brought the ALPR idea forward in 2021, he placed it in the context of reimagining policing in Berkeley, work that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

ALPRs "present an opportunity to reduce property crimes and improve traffic safety while also reducing civilian encounters with police officers conducting ad hoc traffic enforcement," Taplin wrote at the time. "ALPRs could make enforcement more fair, impartial, and effective."

Councilman Robinson, who sat in for Rashi Kesarwani on June 20, said he could see a direct link between vehicle use and "much of the violent crime and gun violence that happens in this city."

As such, he said, ALPRs could potentially be "very relevant" for responding to and reducing crime in Berkeley.

And that could be even more true, Robinson said, when it comes to Berkeley's plans to limit the role of police officers in certain types of traffic stops.

"I don't know that there’s a world where our dream of civilian enforcement for low-level moving violations is effective without mobile ALPR operation," he said.

Robinson said he did have privacy and security concerns that he hoped would be addressed going forward.

On the subject of city spending, Councilwoman Wengraf said the cost of so many stolen vehicles and the potential to crack down on the trend might well outweigh the price of the ALPR system overall.

She said council members would need to take a close look at the numbers.

Wengraf and her colleagues also asked for more details regarding which neighboring agencies use ALPRs and what their systems are like.

Ledoux said Albany is the only other agency in Alameda County that doesn't have them — but he said each city with ALPRs has its own approach, making any kind of comparison challenging.

The officials also asked BPD to work with the PAB and respond to the issues it raised before the item comes before the full council.

Aguilar: How will ALPRs affect racial disparities?

Hansel Aguilar, the city's director of police accountability, also weighed in during the June 20 policy committee meeting.

Aguilar said he hoped to see more information about ALPR locations and questioned whether Berkeley really needs 52 readers.

He pointed to a 2020 survey of more than 1,200 law enforcement agencies in which most of the respondents had "fewer than 10 units" in operation. Just 40% of the agencies surveyed used ALPRs at the time.

Aguilar suggested a better analysis of Berkeley crime data to set goals regarding "what success will look like" and said the city might want to roll out 13 readers annually for several years rather than putting 52 in place at once.

Aguilar said Berkeley also needed to consider how ALPRs might affect existing racial disparities in policing.

"We need to have more conversations about what these technologies are going to do for that," he said. "Are they going to solve these issues or are they going to keep contributing to these issues?"

How to weigh in Thursday: The Office of the Director of Police Accountability will hold a community input session from 6-7:30 p.m. Thursday, July 6. The Zoom link and call-in number are on the city website. See the meeting flier for more details. Once posted, the July 25 City Council agenda will also be available on the city website.